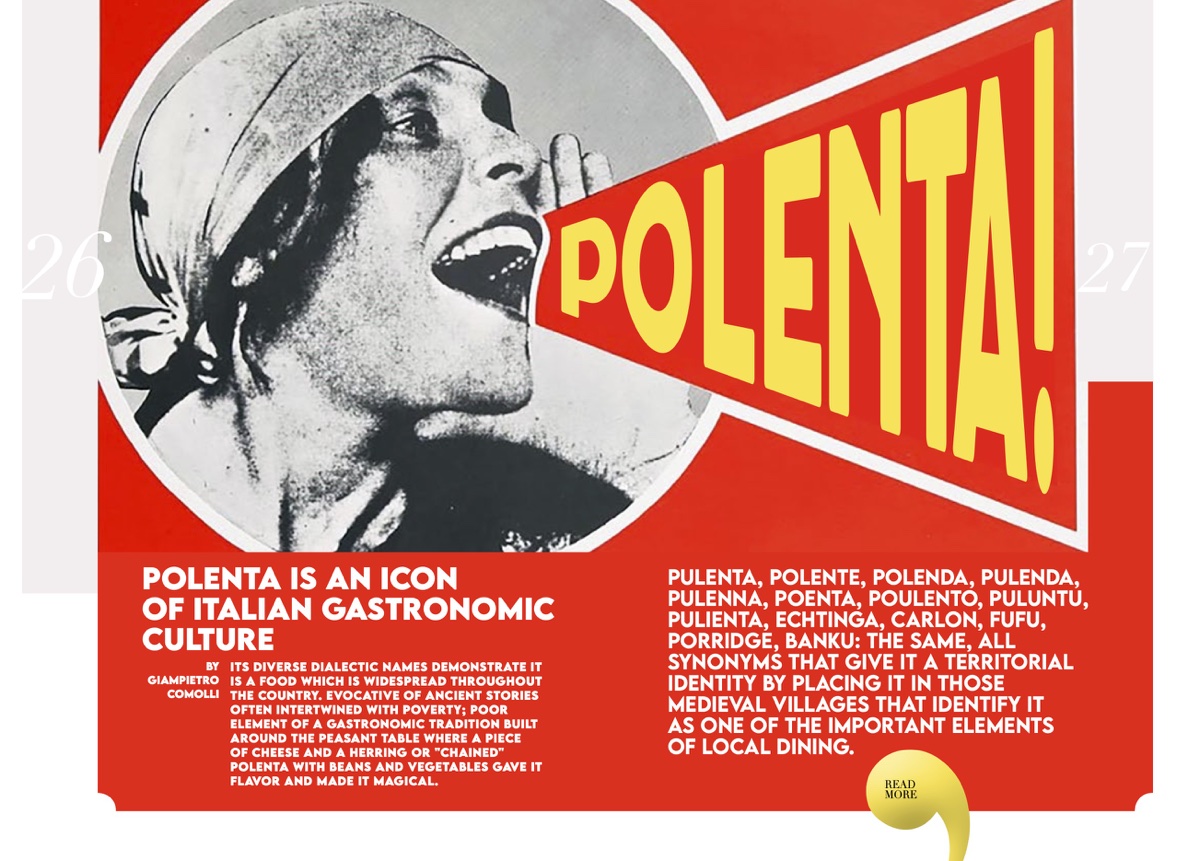

Polenta is an icon of Italian gastronomic culture

Its diverse dialectic names demonstrate it is a food which is widespread throughout the country. Evocative of ancient stories often intertwined with poverty; poor element of a gastronomic tradition built around the peasant table where a piece of cheese and a herring or “chained” polenta with beans and vegetables gave it flavor and made it magical.

Pulenta, polente, polenda, pulenda, pulenna, poenta, poulento, puluntu, pulienta, echtinga, carlon, fufu, porridge, banku: the same, all synonyms that give it a territorial identity by placing it in those medieval villages that identify it as one of the important elements of local dining.

Its secret? Flour and water, the basis of a diet that for at least 4/5000 years has helped to feed the known world, considering the fact that maize flours are only the latest in time order to be used for similar mixtures. I like to think that perhaps the ancient “polenta” was the first creative expression of man’s cooking, marking the transition in his dietary life, from a “raw and gathered” diet to food prepared through careful cooking, which required attention and accuracy like bread.

For millennia, man has mixed seeds, greens and harvested vegetables, pounded in a mortar to obtain a mixture, a paste or a mash that’s more digestible and assimilable.

That was the ancient Italic “puls” also mentioned by Pliny whose preparation, in Campania, involved the use of millet flour. It is in pre-Roman Etruria that a food, “like today’s polenta” originates from the “puls” based on “far” (spelt – in Italian “farro” – from which the Italian generic term for “flour” is derived). A kind of cooked mash, ancestor of bread similar to the “bordei” polenta widespread in Greece, well before the foundation of Rome. The term “puls” could derive from the pre-Latin, pulus, which describes a combination of cereals and dried legumes from which the English term pulses meaning legumes derives in general, which in French becomes pols which always means legumes, like poltos, from ancient Greek, used for a consistent cereal soup. For those ancient polenta cereals such as spelt, buckwheat, oats, barley, millet, sorghum, foxtail millet were used, coarsely ground with stones to which bean, chickpea, pea flours were added to give consistency and density, according to the places and seasons.

The Latin-Barbaric term of “Pultem” had already become “pulenta” in the Middle Ages, at least in local dialect translations, in street tales, in verbal stories passed down. “Pollens” was the term used by the Lombards to indicate mixed soup at the table.

Certainly the arrival of corn has changed not only the agricultural system, diversifying crops, but also the evolutionary processes of a gastronomy that benefited from the use of flours obtained from its own milling.

Those maize-based doughs, loved by the Indians of Central America, were consecrated and consumed on the Venice streets, becoming sweets called “zaleti or zaeti” made with a fine flour mixed with raisins or chocolate. They emerged around 1600 between Belluno and the Friulian provinces of Udine and Pordenone, production areas of the finest corn flour, ideal in the preparation of sweets such as these biscuits, which immediately found favor with the Venetians who loved to dip them in Malvasia and Zibibbo.

But there are a thousand ways to enjoy polenta; in the mountain areas it was seasoned with butter and cheese, whether it be stracchino or gorgonzola, or with fondue; in other parts it was and is still served with beans or smoked herring, with stockfish or cod, with lard or rigatino, with ribs or pig’s trotters, with snout or venison, or cut like a millefeuille and served with onion ragout or anchovies. For these preparations we need soft or hard polenta, dry or slow, straight or “pastizzade“, we need different types of meats, matured in different ways, sea and river fish, mountain or plain cheeses, cold cuts or vegetables, oil and legumes; polenta substantial in taste and the pleasure of tasting it, eclectic, practical, fried or rustic, sweet or savory, suitable for any season, for any palate and for any wine. And so on and so forth. You can be sure that polenta will adapt perfectly to whatever you desire, will not betray you and will be there ready to surprise you.

Today we have a polenta that now satisfies the imagination of gourmets and along the way it has lost the aura of poverty that had accompanied it for centuries.

Its goodness? An organic Italian flour, water and cooking.

Surprise yourselves with simplicity.